How to

Grow

Every business is different, every founder is different.

There is no one size fits all.

The right approach for one business may not be right for another, and even if it was, the founder might not want it. Or the investor might not a good fit.

Despite everything we’ve been through to get to this point in our startup journey, at the end of the day it often comes down to human and relationship issues. I’ve wanted to grow a business faster and take investor’s money, but my partner didn’t. I didn’t want to work with a certain investor but my partner did. I’m happy doing what I’m doing but others might not be… resolving these issues is a key challenge for many new businesses.

At the end of the day you need to do what feels right for you. But take some advice and see what the options are. Perhaps you just need to look at the situation a little differently, or to see what’s possible before you make up your mind.

Some businesses might need to grow fast to survive, others can take their time, some might want to grow ‘vertically’ expanding throughout their supplier and distributor channels, others simply wanting to be the biggest fish in their ponds, and others wanting to be in lots of different ponds… There are no shortage of different ways to grow and different options in front of you.

The fives basic ways are as follows:

The different ways to grow a business:

1 Organically

2 Self-Funded (“Boot-Strapping”)

3 Investor Funded

4 Inorganically

5 “Blitzscaling”

1. Organically

A term for the most typical growth scenario of any business. You do something, your customers pay you for it. Any profit you have left over is used to grow and expand your business. Doing more of what you were doing. Maybe this is opening a new store, designing new products, or hiring new people. The profit generated is used to hopefully make more profit.

Famous examples of organic growth businesses might be Apple or Dyson. They both make hugely successful products and use the profit from those products to create new products.

Organic growth is what most people typically perceive as a good growth policy.

2. Self-Funded

Commonly referred to as Bootstrapping in the US… the self-funded policy is very similar to organic growth, except it refers to startups and projects that are not producing any profit yet.

“Pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps”

- 19th Century expression.

In this scenario there isn’t the profit from a successful product or sale to reinvest. Instead the founding team have to reach into their wallets and pay for it all themselves. This might be from the personal savings or from the income of a second job.

Facebook, Apple, Coca Cola, Hewlett-Packard, Microsoft, Oracle, Dell Computers, eBay, Cisco Systems and SAP were all Bootstrapped startups at one stage.

Cashflow is usually the biggest problem with a self-funded company. The bills keep coming in and if your other income doesn’t match them then you can have problems. As the expression goes:

Revenue is Vanity, Profit is Sanity, Cash is Reality.

3. Investor Funded

Many self-funded businesses go on to become investor funded as they grow. With cashflow being so critical to the survival of any company, there often comes a time where the business just needs more money than it has to do whatever it needs to do. Hopefully thinking ahead rather than needing the money right now!

If you need the money urgently, then it’s unlikely you’ll get the best price for what you’re giving away: shares (equity), control and influence over where you take your business. In exchange for what you hope to receive from any investor lead funding: money, a possibly easier route to more money if needed in the future, expertise and a bigger network.

Different types of investors tend to operate for different sizes of businesses at different stages of their lives. For people just starting out, the usual first door founders knock on for money is known as the “Three Fs”: Family, Friends and Fools… I’m not sure I agree with the use of the term Fools, it’s a little too derisory for people wanting to invest in a very early venture and sounds to me like it was an expression made from a later stage investor. But given the very low chances of success in these early days, there is some credence to it.

A term for people wanting to invest very early in projects, but who also tend to be more hands on with the business and have lots of experience to bring to the table is: Angel Investors.

Typically rich individuals who have some spare money and enjoy risking it on early ventures because they love the thrill of helping founders get off the ground.

Next is Venture Capitalists… these people can have huge amounts of money at their disposal, but they are looking for ventures that have or may soon find Product / Market Fit. The dream for a venture capitalist is to be able to pump money into a proven business model that is not yet well known about. Every dollar in has an exaggerated impact on the companies rate of growth and profitability.

Finally, institutional investors, the Hedge Funds, Mutual Funds and Endowments sitting on billions of other peoples money (such as a pension pot) and are looking for companies that are big, established and look like winners. Of all the investor types described they want the lowest risk, but have the most money to play with.

This is something we’ll come back to in the Financial markets introduction but from the point of view of growing your business, it’s probably impossible that you’ll get the attention of an institutional investor until you’re a FTSE100 (or equivalent) company.

4. Inorganic

As we’ve said before, companies can grow with any number of strategies, start self-funded, then become investor funded and then grow with a combination of organic or, as we’ll explain here, inorganic growth.

Organic is the often slow progression based on the natural expansion caused by an increased demand in your offerings. Inorganic is the accelerated growth caused by the acquisition of another company. Rather than expanding my coffee shop in Bath, what if I just bought a rival Bath coffee shop? I’d now be twice as big, but this growth is considered inorganic and comes with lots of risks and benefits.

Microsoft is a famous example of a company that likes to grow inorganically, purchasing over 240 companies completely and buying stakes in another 100 over the last 30 years. (By comparison Apple has made 120 similar investments over the same time period.)

The typical language for this is Mergers and Acquisitions and there are many big banks and consultancies that specialise in helping companies with this process as it often requires raising a large amount of money to complete the purchase and then lots of advice in how to blend or absorb a different workforce and work culture.

“Blitzscaling”

Winner takes all rapid expansion to total domination…

Coined by the legendary Silicon Valley figure Reid Hoffman in his book by the same name, Blitzscaling is a term he created for funding and growing technology startups very quickly in a winner takes all situation. In his own words:

“Blitzscaling is what you do when you need to grow really, really quickly. It’s the science and art of rapidly building out a company to serve a large and usually global market, with the goal of becoming the first mover at scale…

The theory of the blitzkrieg [from the first and second world wars] was that if you carried only what you absolutely needed, you could move very, very fast, surprise your enemies, and win. Once you got halfway to your destination, you had to decide whether to turn back or to abandon the lines and go on. Once you made the decision to move forward, you were all in. You won big or lost big. Blitzscaling adopts a similar perspective. If a start-up determines that it needs to move very fast, it will take on far more risk than a company going through the normal, rational process of scaling up. This kind of speed is necessary for offensive and defensive reasons. Offensively, your business may require a certain scale to be valuable. LinkedIn [a company founded by Reid] wasn’t valuable until millions of people joined our network. Marketplaces like eBay must have both buyers and sellers at scale. Payment businesses like PayPal [also with Reid as a founding member] and e-commerce businesses like Amazon have low margins, so they require very high volumes. Defensively, you want to scale faster than your competitors because the first to reach customers may own them, and the advantages of scale may lead you to a winner-takes-most position. And in a global environment, you may not necessarily be aware of who your competition really is…

Blitzscaling is always managerially inefficient—and it burns through a lot of capital quickly. But you have to be willing to take on these inefficiencies in order to scale up. That’s the opposite of what large organisations optimise for.”

Blitzscaling is not something you can do by yourself, and Reid is speaking from the point of view of an investor in tech startups, so he’s keen to attract opportunities to him that want to follow this path. But it requires constant injections of cash from investors and typically the founder will spend as much of their time finding new money as working on the business itself. If done right and in the right circumstances, the outcome can be dramatic.

Snowballs

Business momentum, hype and how to think about attracting investment.

Investment attractiveness is a bit like a snowball rolling down a hill…

If you’re looking for investors, ideally you want them to be fighting over you, fighting over who can give you the most for the smallest share in your business. But in order to attract investment at all you have to show that your company is making progress to its ultimate potential. Like a snowball picking up more snow and getting larger as it rolls, gathering momentum and size as it goes… The faster and further you move, the bigger you get and the more excited investors will be to give you more money to keep that roll going.

Blitzscaling is about turning that snowball into an avalanche, an unstoppable momentum that engulfs everything in front of it and through sheer force of nature attempts to guarantee success.

Your value as a startup with a still unproven business model is largely a factor of this momentum, if things seem to be going well, number of customers increasing, revenue increasing, amount of press increasing etc… everything that feels like forward progress seems to be on the up, then investor excitement and interest will also increase.

If on the other hand, you have a good initial flurry of activity but it looks like you’ve lost momentum, you may struggle to find investor interest or for a good price.

Managing this moment, or appearance of momentum is an important consideration for founders looking for investment.

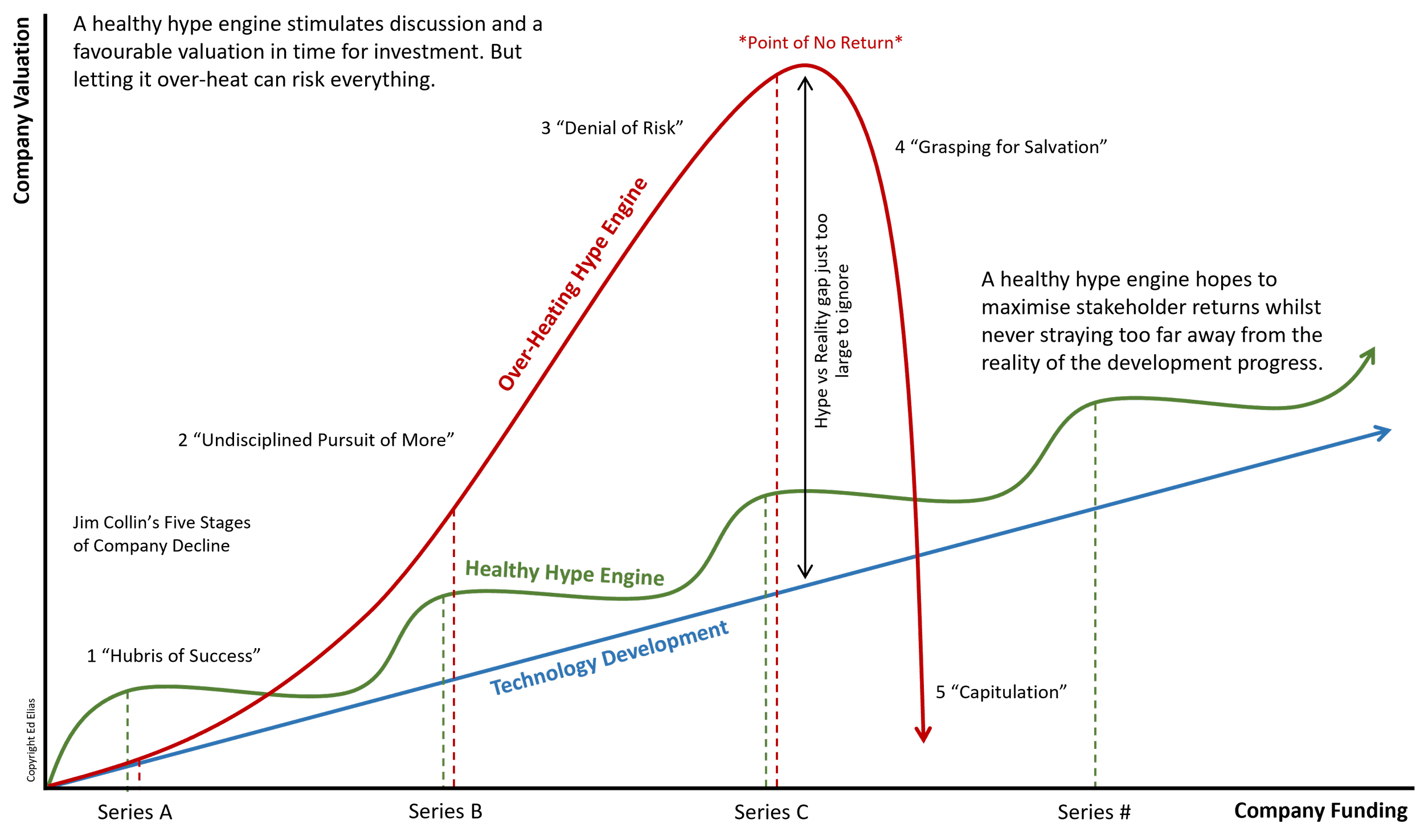

Controlling the “Hype Engine”

For many start-ups, hype, the illusion of something more significant than it is, is a central pillar of their strategy for growth. To “hype something up”, to “fake it till you make it” are all ways to get the proverbial snowball rolling. But without trying to mix up too many metaphors, the risk is that the snowball takes on a life of it’s own, one that you can no longer control.

Founder’s should look to control the excitement around their business, without letting the power and success that can sometimes come from this going to their heads.

Elizabeth Holmes (of Theranos infamy) kept pushing the fake it till you make it mantra far beyond what was morally or legally acceptable. So whilst it may have been possible for her technology start-up to one day achieve what it claimed it could already, far too many powerful people (with too much money at risk) were left with unanswerable questions that it had to be investigated.

The list of founders who let their, or even encouraged, their ‘hype engines’ to overheat is extensive. Adam Neumann of WeWork who would have had you believe that he was on the verge of a complete technological revolution, rather than a simple office leaseholder. Or Trevor Milton of Nikola who fooled GM into investing billions by pushing a truck down a hill and claimed it was driving on green hydrogen electricity.

So the logic of a healthy hype engine is that it should be pumped to build investor interest before you need to fund raise. But as soon as the necessary funds are in the bank, focus everything on lifting your offering up to the level the investors hoped to see. They were betting on potential and you better start showing some progress towards that. It overheats if the gap between what your promising and what you’re actually delivering becomes inexcusably wide.

Do:

Build momentum and control a healthy degree of hype when you need it

Don’t:

Get carried away with your own fairy tale and forget none of it is yet real.

Forget the hype engine can continue without you, the right fuel may cause it to overheat even without you constantly stoking it. So be prepared to dampen it down.

The failure of a overheating hype engine matches closely to Jim’s Collins’ five stages of corporate decline. Read his book, How the Mighty Fall for more info, you have been warned!

Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding is not a new idea, but it has really surged in popularity through some very well designed web platforms. Typically it is used to raise money at early stages in the life of a company or product. For example, lets say I’m thinking of opening a new coffee shop in Bath specifically targeting cyclists (bikes on the walls, bikes hanging from the ceiling, chairs made of bikes, a bike workshop on site and discounted drinks for anyone who arrives with a bike… you get the idea). Rather than go to all the expense of actually doing it, only to discover no one turns up (Bath is maybe too hilly). Maybe I could organise a crowdfunding campaign beforehand and see if anyone is interested and not only that, raise some money to help me buy all the decorative bikes I’m going to need.

There are two basic types of crowdfunding:

1. Money in exchange for something

A free drink at my coffee shop, or an engraved chair with your name on it, or a cookie named after you maybe?

Examples of such sites include:

Kickstarter - a curated list with some checks in place

Indiegogo - pretty much anything goes

2. Money in exchange for shares in a company (maybe with some as well as a bonus).

You can be a shareholder so when starbucks comes crawling up to us begging us to put them out of their misery, you will be handsomely rewarded for trusting me at this early stage… plus have one free drink a month.

Examples of such sites include:

Should you do it?

If you have a prototype product then it’s certainly a tempting option. Some large investors even insist their investments launch a crowdfunding campaign to prove the demand is there. If it’s a success then they will give the startup more funds, if not, then goodbye.

If you’re a small business needing to raise cash, you can get a better valuation as the crowd may not be as informed or as demanding, especially if it’s a gimmicky on trend idea, like anything bitcoin related was last year. But you might end up having to deal with 1000s of investors, all demanding your time and wanting to know what’s going on.

What about banks?

No free lunch…

Banks have a simple rule: lend to people who can pay it back, or have something valuable we can take if they don’t.

So homeowners can usually borrow money quite easily (mortgages) because if you don’t pay it back, they can take your house. So whilst it’s common to think a bank might be able to help you with growing your business. It’s unlikely they will want to unless you have something to guarantee the loan.

Rich people who don’t need more money can borrow from banks very easily, whereas people who actually need it often struggle. Sorry, I don’t make the rules.

So it’s pretty unrealistic for a bank to lend a new business money.