“If business was a car and money was the fuel, the aim of a business is not to have the most fuel but to go the furthest along your journey.”

Simon Sinek [abridged]

The History & Purpose of Business

The word “company” came from the first professional armies of the ancient world. A company of soldiers would have an identity, a banner, a standard, a name and whilst the soldiers in that company might change over time, the company would stay the same.

If you’re a fan of old TV shows, Trigger the road sweeper from Only Fools and Horses summed it up well: “I’ve maintained this trusty broom for 20 years. It’s had 17 new heads and 14 new handles in its time.”

This company of soldiers also had materials and resources that were specifically for it, owned by the company, not the individual members within it. Equipment, weapons, horses, wagons, clothing etc… When a new recruit joined they didn’t bring their own gear, the company would provide it. This idea of a thing, rather than a specific human being, owning stuff would have an profound impact on the way people thought of organising themselves to achieve things outside of efficient military organisation.

Some of the oldest companies that are still in business today.

But the idea of what a corporate, money making company is today has been changing. The profit above all else mantra of the 70s and 80s is finally giving way to a more people and planet first approach. Serving society. employees and shareholders rather than only the shareholders.

Soldiers might fall and be replaced but the company lives on.

Types of Economy

The way civilian companies (from now on I’ll drop the need to say civilian and will use the word companies interchangeably with the word businesses) act within society as a whole to generate economic activity, the flow of money and goods, has changed back and forth a lot through history. Different societies have had different rules and different ways of thinking about the system as a whole. Today we tend to see a mix of these four:

A Free Market Economy

In today’s world this is probably best represented by the US way of doing things. Basically you can do whatever you want, if people want what you do then they will pay you for it. The price is agreed between you and the person wanting the service. Very little if any involvement of any overriding authority figure. Possibly one of the best examples of a free economy in history might be periods of the Roman Empire, where almost everything was operated by private civilian companies (called “Publicans”). If they had conquered a new province, private companies would bid for the contract to raise new taxes in that region or run government services. If your soldiers were fighting in a far flung region, private companies would bid for the contract to supply those soldiers with food.

In theory, because anyone can do anything there should be fierce competition between companies out bidding each other for your attention which should lead to a higher quality, cheaper prices and more variety.

This economic system is the basis of capitalism and the two terms are often used interchangeably:

“an economic system characterised by private or corporate ownership of capital goods, by investments that are determined by private decision, and by prices, production, and the distribution of goods that are determined mainly by competition in a free market.”

A Command Economy

A system where there isn’t free choice, what you have is dictated to you by an authority figure. The Soviet state plans are a great example. Today we need steel, everyone go an make steel… Tomorrow we need wheat, everyone become farmers. There are no private companies, everything is owned and controlled by the state.

So whilst everyone should have a job there is the potential for large inefficiencies if it’s not organised very carefully, fixed prices for everything and a lack of choice. I visited Cuba in 2007 and large beautiful shoe shops that were built before the communist revolution would be almost bare inside with only a single pair of shoes in the window.

A Mixed Economy

As you might guess from my lead up to this, a mixed economy is a blend between Free and Command. There are private companies and they can do many things but they must follow some rules and inspectors or governing bodies will check that you are following them. There may also be state run organisations that act like companies but are run by the state (the NHS being a good British example). Which in some people’s eyes give them an unfair advantage.

This, to varying extents, is how most of the world works today. Some places have stricter or looser rules, some places are corrupt, some less so, but generally you can do what you like if you play by the rules. Free Market economists don’t like these rules they think you don’t need rules because society will reward ones it likes and punish (by not buying their goods or services) the ones it doesn’t.

The UK is a mixed economic system, generally free, with little corruption, but as a society we like having some rules in place (minimum wages, anti-monopoly rules, consumer protections, government bail-outs for struggling companies that are deemed to be in the nation’s interest to save) so while we consider ourselves a free economy, we’re technically a mixed system.

Self-Sufficient & Manorialism (Feudal) Economies

Self-sufficiency is what it is, you don’t have a choice unless you give yourself one. There may not be a market for you to go and buy or trade goods. If you don’t grow it or make it yourself then you won’t have it. Tragically a lot of the world still live in this environment and are hugely vulnerable to weather conditions, poor soil, famine and poor health.

A similar variation on this, that is not common any more but was prevalent throughout the last 1,500 years of European history is the Manorialism system. The ruler would divide up their land and give different bits to their nobles, the various lords and ladies who were their friends. These nobles would then divide up that land even further and issue it to the farmers and lower classes who lived on the land. In exchange for being able to support yourself and your family you would have to pay money or give a portion of your produce to the noble. They would then redistribute it, sell it or do whatever they wanted with it. This was self-sufficiency but with a community and that hopefully produced a surplus. The good nobles would support their people and use that surplus income to make the whole community better so that in turn they could produce more and survive future poor harvests. The bad ones might just be tyrants and exploit their poor people for a short term benefit.

So there are elements of a mixed economy here but with an overriding flavour of self-sufficiency.

Not always quite what they seem.

It’s easy to think that once you’ve seen something somewhere, it will be like that everywhere. A related example that struck me was from a trip to La Paz in Bolivia. Walking the city I turned a corner and found a whole street of people selling oranges. Piled high. It didn’t make any sense to me, the oranges all looked the same. How can any of these market traders compete with each other? All the power is in the hands of the customers, if you don’t like the price, take two steps to the right and speak to the next trader. Turning another corner there was a whole street selling paint, another selling underwear, and so on and so on…

It seemed very counter-intuitive to me and as I continued my explorations of the city I discovered that it was very hard to find an orange anywhere but on this street. If you want oranges you went to that place. Everyone knew it.

If you opened a shop selling oranges anywhere else, people wouldn’t trust you, who is this person, why are they not with everyone else where we can haggle and compare prices? They must have high prices… As well as people thinking your price must be higher, it probably will have to be. It’s much cheaper to get your oranges delivered to the same place everyone always delivers oranges. You in turn are buying your oranges off suppliers and if all the suppliers and traders are in the same place, the power is now in your hands.

It’s a free market situation but society norms, habits, established ways of working have instilled rules and systems that may be hard to break.

These established ways of doing things are everywhere, often not talked about, they’re so normal you don’t even realise and go unnoticed. There may be a good reason for them that you can’t change or it maybe that the reason has long vanished and all it takes is a fresh thinking pair of eyes to notice and want to break the mould. Most efforts to do this will fail, but sometimes you’ll look back and think, wow wasn’t it strange that we always went to the same street to buy oranges…

Stocks & Shares

Companies have been around for thousands of years, but in different periods of history, society viewed things differently. Early Christian Europe saw the lending of money in with the promise of interest as an immoral act (usury) and so exchanges of money for shares in your venture was a good alternative to raising the necessary funds.

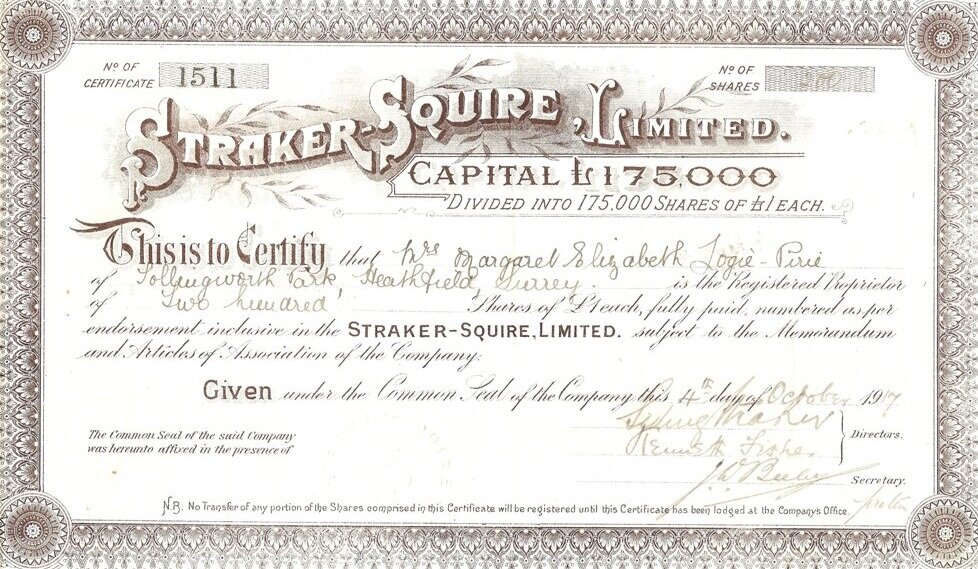

The sale of shares of stock, company stocks, shares, equity, whatever you call them, is a method of raising money without borrowing or having to pay interest. The company simply puts up for sale a portion (a share) of their company and negotiates a price.

If you buy it, you get a certificate detailing the size of your portion (1 share, 1,000 shares, whatever it may be). In the future the company might want to buy it back off you, or you could sell your share to someone else. The hope being that if the company has done well, more people would want to buy portions of that company than there are people who want to sell and so the price you can negotiate for it will rise. If no one wants to buy your share when you want to sell it, then you’ll have to accept a much lower price and this reflects badly on the value of the whole company.

In essence this is a mini example of free market economics. Prices can go up and down depending on what people are willing to pay and since share ownership doesn’t normally come with any perks it’s speculation on the future value, rather than any usable service now.

Walk through example…

If you start a company by yourself, then by default you own it all, all the shares (typically just 1). At some point in a company’s life, the owner(s) may wish to sell shares to a few private individuals or they may wish to sell shares to the general public (splitting up that original 1 into hundreds, thousands or millions etc...).

But once your shares are freely sold on the open market (a stock market) to the public, the value of your company is clearly visible to everyone and it may affect how easily you can raise money from banks and lenders. Valuable companies get good borrowing rates, companies whose value has been falling recently might not.

Sometimes more valuable companies will buy all the shares of less valuable companies or rich individuals might do the same. Taking the company off the market and back into private ownership. This is often done when buyers feel that the price of a company’s stock does not reflect the true value and it’s stock market traders (or cynically market gamblers) who are using abusing this company’s share price as a way to make quick money, rather than the more moral goal to support its business efforts.

Remember, business is a car on a journey. Good companies should have a good destination in mind and money is the fuel to get you there, not the destination itself.

We’ll talk more about this in our discussion on finance and the stock market.

Guilds, Charters and Staples

Perhaps not so relevant today, but back in ye olde times when kings and queens ruled the European world, communication methods between people weren’t as easy as they are now and people were more comfortable with simple one-size-fits all rules coming down from the person at the top. Local or national tradespeople might form themselves into groups, all the plumbers in Bath for example, might get together and say if you’re not part of our club, cynically you might associate this sort of thing with a mafia family and some sort of protection racket, then you can’t work as a plumber in this city.

In their defence they would say that they are ensuring a high level of quality, might offer their members benefits such as insurance or a pension but it’s easy to see how today it could be seen as price fixing or removing customer choice. Two things that are either illegal today or definitely frown upon by the authorities in our Mixed Economy world.

But many of these clubs became officially endorsed by the rulers of their time and became Royally approved ‘Guilds’. Essentially an early form of trade union, local mafia family and political lobby group rolled into one…. Lets say the fictitious plumber’s guild of Bath might want me to introduce a few new rules making it illegal for anyone to be a plumber in Bath unless they are a member, and in exchange they’ll give me a regular cut of their earnings (we’ll call it a plumbers tax) and a brand new local invention…the flushing toilet. Sounds like a good deal if you have no real way of knowing what’s going on.

The big advantage to arrangements like this for early rulers was it kept things simple. I can collect taxes from all the different Guilds around the country and they will ensure no one breaks the rules because it’s in their self-interest to do so.

A more extreme example of this is in the form of Royal Charters and Staples…

Royal Charters

Very simply, rules that mean if you wanted to do something, only the person with the royal charter to do that thing could do it.

For example if I had a royal charter (permission from the Queen) to sell coffee in Bath. Only I or those who have my permission could do that. Anyone else (Starbucks, Costa etc…) would be breaking the law and I could shut down their stores, seize their beans and run them out of town.

Since everyone in Bath loves drinking coffee, this royal charter would be really valuable and may mean I have a big enough income to fund my own private coffee police to enforce these rules and keep the Starbucks and Costa gangs away.

Staples

Very similar in idea to a royal charter (and setup through a royal charter) but this time usually referring to actions and transactions in a specific place. For example in 1363AD the newly conquered (by the English) city of Calais had a staple on wool exports from England. Meaning every wool export from England had to go through Calais first and had to pass through one of the 26 officially endorsed Staple Merchants (middle men) there who would take a cut and in return pass a portion of that (a tax) to the King.

Different towns and ports might have different staples and it made it very simple for the rulers to monitor what was going on and to earn money because everything was (meant to be anyway) happening in just one place.

The East India Company Flag

(Not enough companies have a good flag these days)

The East India Company was a private company, registered in London and whose stocks anyone could buy and sell on the stock market. But it’s unique selling point was its Royal Charter from Queen Elizabeth I to all income from the east of the Cape of Good Hope (the southern most tip of Africa) and west of the Straights of Magellan (southern most tip of South America).

This was back in the day when Western European Nations weren’t really sure what opportunities there were in Asia, but the first sea routes around Africa had opened up and everyone was racing to get there to find out. In 1600 a group of merchants asked the Queen for a Royal Charter for their expedition. Up until 1874 the British effort, led by this company, the later named the East India Company, came to dominate the region, conquer and rule most of South Asia and at it’s peak had an army of 260,000 men and accounted for half of the worlds trade.

Yes, 50% of all world trade went through one private company with one large private army. Eventually though it ran into financial trouble and a new government law (the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act) took the company into government control, absorbed it’s private army and navy into the British forces and assumed control of its territories.

Some modern business context

If you read the business news, it tends to be all about the large companies, and for obvious reasons that makes sense (they are a big chunk of UK employment) but they are a surprisingly small part of the UK business scene… The reality of business in the UK is quite different from the impression you might get in the news.

99+% of businesses are smaller

There are around 2.8million active companies in the UK and so the big business list of the FTSE100 which is often referenced as to the health of business in the UK is around 0.00004% of active businesses.

Most do not have shares you can publicly buy and sell.

The slightly misnamed FTSEAll-Share. represents around 1000 companies and the “Alternative Investment Market” holds another 3,500. So that leaves quite a few (to put it mildly) not listed on any UK stock market. They may have shares you can buy and sell, but it would be done privately between you and the company.

SMEs are 60% of all employment

Small and medium sized businesses (SMEs) are companies with less than 250 employees.

75% of SMEs employ only 1 person

If 99% of businesses are SMEs but 75% SMEs employ only 1 person then basically 75% of all businesses are single owner operators and 25% of employment is held by a tiny number of large companies.

Only 34% are registered limited companies (Ltd)

In the UK, when people refer to setting up a company, they often mean a Limited one and would have Ltd after their company name. This is typically thought of as ‘proper’ company and gives the shareholders some extra legal rights and duties. 6% are partnerships (typically GP practices or legal firms) and the rest (60%) are sole-traders. A sole-trader is basically another word for self-employed. To all intents and purposes there is effectively no difference between the two terms.

Plc, Inc, LLC…

In the UK, if your company is registered on a stock market, so that the shares can be publically bought or sold, your company will have PLC (public limited company) after it’s name, Vodafone Group PLC for example rather the Ltd (private limited company). The US equivalent of a PLC is an Inc (Incorporated and thus often referred as Corporations rather than businesses) and Ltd is an LLC (limited liability company).